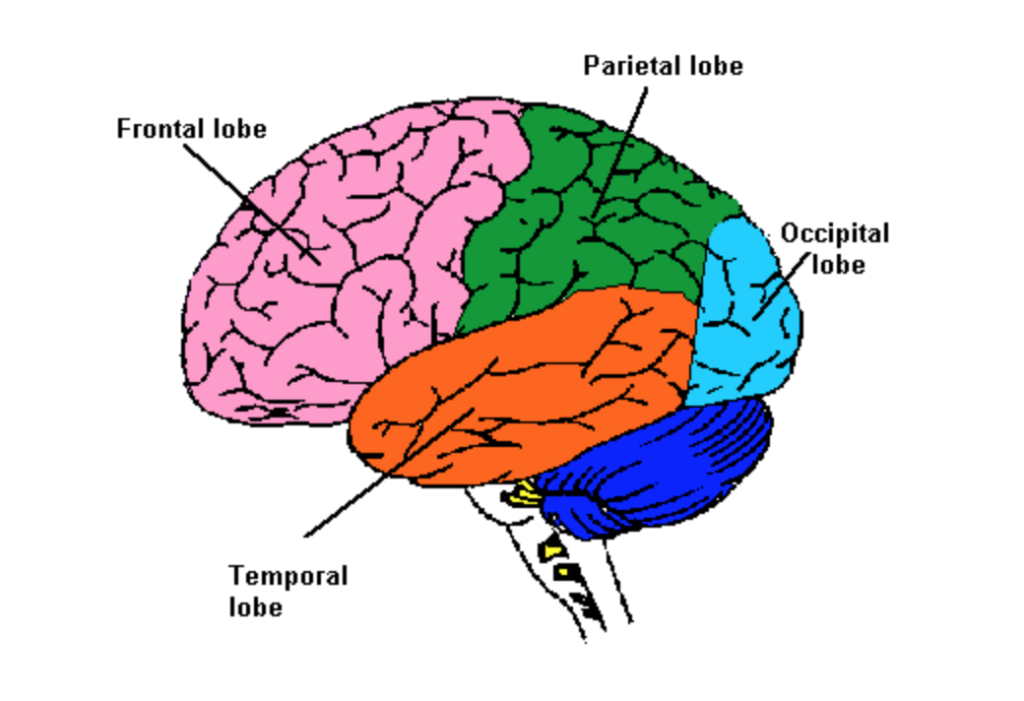

Cavernous malformations (also known as cavernoma, cavernous angioma, or CCM) may appear anywhere in the brain, but they are most often found in the supratentorial region. This area includes the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes.

Cavernous malformations in these areas can trigger seizures. It is thought that cavernous malformations trigger seizures by irritating the surrounding brain tissue. Likely, the irritation is caused by blood oozing from a lesion.

Epilepsy is the term used to describe the condition in which a person has ongoing seizures. People with cavernous malformations can develop epilepsy as a result of their lesions.

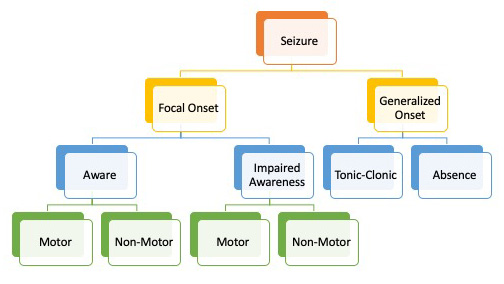

Seizures can be divided into two groups: focal onset and generalized onset. A focal onset seizure starts in one area of the brain. This is the typical seizure found with a cavernous malformation. Seizures usually originate near a specific lesion. With focal onset seizures, individuals remain aware of their surroundings or they may experience impaired awareness. In both cases, their seizures may be motor or non-motor.

Focal Onset Seizure

Focal onset seizures are contained to one area of the brain, near a lesion or surgical site. The symptoms of the seizure are determined by the lobe of the brain in which the seizure is located. Below are lists created by Epilepsy Action of typical seizure symptoms associated with each lobe of the brain.

Frontal Lobe

Frontal lobe seizures may happen during sleep, often in clusters. If a frontal lobe seizure happens while awake, it can be mistaken for mental health or behavioral issues. Symptoms can include:

- Pelvic thrusting, kicking, thrashing, or rocking movements

- Screaming, swearing, or laughing

- Unintentionally passing urine (urinary incontinence)

- Your head or eyes turning to one side

- Having unusual body movements, such as stretching one arm while the other bends

- Twitching, jerking, or stiffening of muscles in one area of your body. The movements may sometimes spread bit by bit to other areas

Occipital Lobe

Symptoms of occipital lobe seizures include:

- Seeing flashing lights, colors, or simple patterns

- Seeing more complex images, such as pictures of people, animals, or scenes

- Not being able to see as well as usual, or not being able to see at all

- Eye movement you can’t control, such as your eyes closing, moving to one side, or rapidly moving from side-to-side

- Eyelid fluttering

Parietal lobe

Symptoms of parietal lobe seizures include:

- Having feelings of numbness or tingling

- Prickling, crawling, or electric-shock sensations, which may spread along the affected body part

- Sensations of burning, cold, or pain

- Feeling like part or all of your body is moving or floating

- Feeling like a body part has shrunk, enlarged, or is missing

- Sexual sensations

- Difficulty understanding language, reading, writing, or doing simple math

- Seeing things as larger or smaller than they really are, or seeing things that aren’t there

Temporal lobe

Temporal lobe seizures are usually focal impaired awareness seizures. Lesions in the temporal lobe tend to cause epilepsy (TLE) more than lesions in other areas. After a temporal lobe seizure, it’s not uncommon for a person to feel confused. Symptoms can include:

- Feeling frightened

- Feeling like what’s happening has happened before (déjà vu)

- Hearing things that aren’t there

- Experiencing an unpleasant taste or smell

- Having a rising sensation in your stomach

- Lip-smacking, repeated swallowing or chewing

- Changes to your skin tone or heart rate

- Automatic behaviors such as fidgeting, undressing, running or walking

Focal Aware versus Focal Impaired Awareness

There are two types of focal seizure: focal aware and focal impaired awareness. Each of these can be primarily motor or non-motor.

Focal Aware Seizure

Formerly called a simple partial seizure, in a focal aware seizure, the person stays aware of what is happening around them. They are unable to stop their experience or behavior. The seizure behavior depends on the area of the brain affected. The seizure can result in such things as intense feelings, uncontrolled movements, vision problems, or speech problems.

Focal Impaired Awareness Seizure

Formerly called complex partial seizures, in a focal impaired awareness seizure, there is a loss of awareness and the person engages in “automatisms” – behaviors such as chewing, swallowing, picking at clothes, or scratching.

Motor versus Non-motor seizure

This is an additional description of a focal seizure. In motor seizures, the activity during a seizure primarily involves movement like jerking or twitching. In non-motor seizures, the person experiences changes in emotions, thinking, or sensations.

Generalized Onset Seizure

Generalized seizures involve both sides of the brain from the start. A focal seizure can sometimes generalize to other areas of the brain, but this is not the same as a generalized onset seizure. Absence seizures and most tonic-clonic seizures are generalized onset. Tonic, myoclonic, and atonic seizures can be either generalized onset or focal onset.

Absence

Also known as a “stop and stare” seizure. The person having the seizure stops what they are doing and blankly stares into space. The person is not aware that they have had a temporary interruption of their activity.

Tonic-Clonic

Formerly known as “grand mal”. This is what people usually think of when they hear the word seizure. During a tonic-clonic seizure, a person loses consciousness, falls to the ground, and may stop breathing for a short period. They may have a period of jerky limb movements after which they go limp but remain unconscious. Gradually, the person regains consciousness and will likely feel very tired.

Myoclonic

Myoclonic seizures, also known as myoclonic jerks, are brief twitches or spasms that can involve all or part of the body.

Pseudo-Seizure

Pseudo-seizures are also called psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES). According to the Epilepsy Foundation, about 20% of people referred to epilepsy centers are eventually diagnosed with pseudo-seizure. Despite their name, pseudo-seizures are as real as epileptic seizures, but their cause is not the same. Symptoms of pseudo-seizure often include:

- Jerking motions

- Falling

- Body stiffening

- Loss of attention

- Staring

Pseudo-seizures can be caused by stress, trauma, or a variety of psychiatric conditions. Typically, treating the underlying condition will resolve the pseudo-seizures.

Diagnosing Cavernous Angioma Seizures

Seizures are, for the most part, diagnosed clinically, based on patient and family member report of symptoms. Further testing can help your doctor understand the source and characteristics of the seizure.

With a focal seizure, testing should always include MRI to identify the type and location of the lesion causing the seizure.

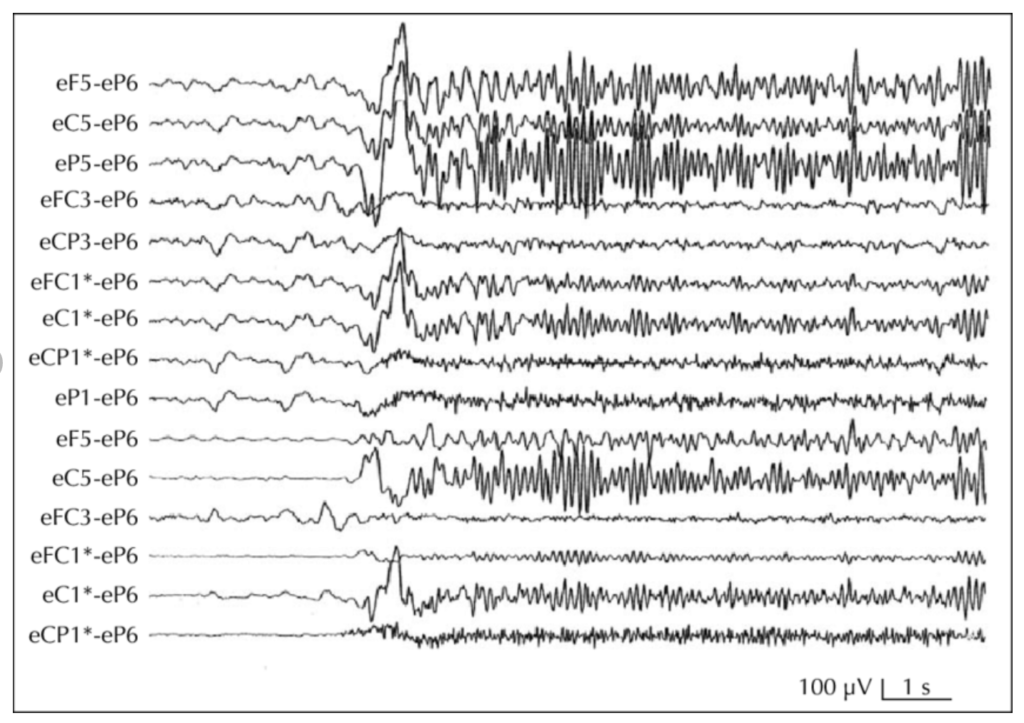

An EEG measures the electrical activity in the brain, which is visualized as brainwaves. During an EEG, electrical sensors called electrodes are pasted onto your scalp and connected by wires to the EEG recording machine. The electrodes only record what is happening in your brain; they do not emit anything and do not cause pain.

If your brainwave patterns are different from other people’s, this is caused by electrical activity in your brain. This may show that you have epilepsy. However, if you do not have a seizure during your EEG, there may be nothing unusual to see. An EEG can identify a seizure when it happens during the EEG, but it can’t rule out that you may have seizures at other times.

EEGs may be performed for varying lengths of time and under varying conditions. You may have an EEG on a typical day, while sleep-deprived, or during sleep. Your EEG may last an hour, or you may have an ambulatory EEG which could last 36 hours or more. Your neurologist can explain why a particular EEG was chosen for you.

Medication versus Surgery

If you are diagnosed with epilepsy as a result of cavernous malformation, you and your neurologist and neurosurgeon may discuss more than one treatment option.

Medication. For many people, anti-seizure medications are able to reduce or eliminate seizure activity. It may take a trial of several medications before finding one that both controls your seizures and has minimal side effects. Anti-seizure medications only work when you take them. If you stop taking your anti-seizure medication, you risk having a seizure.

Surgery. Brain surgery is effective in stopping seizures, particularly if it is performed within the first two years of a first seizure. It is also more effective for those who have only one cavernous malformation.

To remove a cavernous malformation that is causing seizures, a surgeon may opt for traditional open brain surgery or, if the lesion has not hemorrhaged, for minimally invasive laser ablation. There are varying opinions on whether removing the surrounding hemosiderin-stained tissue is required for seizure control. Your neurosurgeon can share with you the plan for your surgery.

Patient story: Stacie

Stacie awakened in the middle of the night, just like many other nights. Only this time, as she tried to walk across the room, she became unsteady and fell into the wall. The dizziness happened again the next morning. A 36-year-old mother of four, Stacie sought medical help, but after numerous tests, the doctors were unable to provide her with a diagnosis.

Stacie awakened in the middle of the night, just like many other nights. Only this time, as she tried to walk across the room, she became unsteady and fell into the wall. The dizziness happened again the next morning. A 36-year-old mother of four, Stacie sought medical help, but after numerous tests, the doctors were unable to provide her with a diagnosis.

One evening a year later, Stacie experienced what she later would learn was a series of focal impaired awareness seizures that included involuntary movement, a loss of awareness, and difficulty speaking. Her husband rushed her to the local hospital where a CT scan revealed an unidentified mass deep in her right temporal lobe.

Stacie transferred to a larger hospital with more advanced diagnostic capabilities where she received an MRI. Her brain mass was diagnosed as a cavernous malformation, and she was discharged on anti-seizure medication. Despite this, the seizures continued, and she sought a surgical consultation. The doctors informed her that removing her lesion would be difficult because of its deep location, and surgery could cause additional harm. Stacie needed to accept her new normal.

It has been a year since her diagnosis. After trying a few different anti-seizure medications to find the best fit, Stacie’s seizures are now under control. She says she has learned to leave her high heels in the closet because she still experiences dizziness. Sometimes she has trouble finding the right words. “It’s like playing charades with my kids,” laughs Stacie. “Eventually they figure out what I mean.” She is happy to be driving again and to be able to take care of her family.

Says Stacie, “My brain hemorrhage changed my life, but I know there’s a reason. I will use it as a strength and not a weakness.”

Last updated 4.16.22